Forgive me for being a bit brash, but if I were to make the title more palatable it wouldn’t convey the same meaning. Le Corbusier really did fuck it all up.

Who is this guy, you might ask? Aside from architects and students who have taken architecture classes, few seem to recognize his name. Le Corbusier, a pseudonym he gave himself, was an early twentieth century architect obsessed with engineering as architecture, concrete, steel, height, cubism, and urban planning.

So what’s the big deal? Here’s the thing: every single time you walk into or around a poorly colored, boring, square or rectilinear building in an urban setting that is utterly devoid of feeling and emotion, you are seeing a poorly copied and executed derivative of his work. He is the reason that urban and suburban commercial curb cuts alike seem completely devoid of soul.

Want some provincial examples? How’s this beauty, which I see on my way to the gym:

Or this one, in which my accountant has his office:

Who thought of these awful places, you might wonder? 20th century architects operating under urban planning authorities, both trying to copy and implement Corbusier’s ideas. Maybe you’ll recognize some similarities in Corbusier’s work:

In Brazil:

In Japan:

In India:

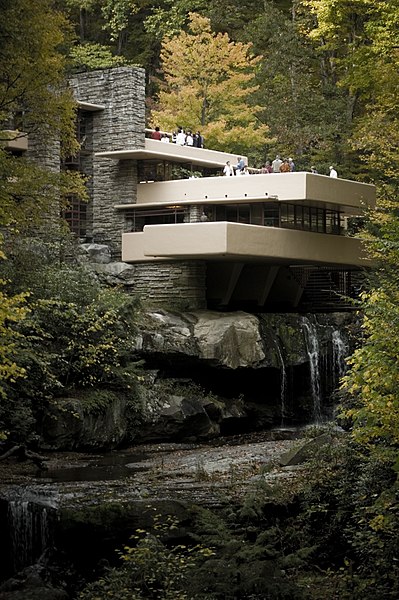

Corbusier originally worked with the inventors of reinforced concrete, and he constantly reused it in the facades of his buildings. He also experimented with cubism and purism. Neither of these are particularly bad. Other delightful architects also worked with very pure geometric forms. Frank Lloyd Wright immediately comes to mind. Both his Guggenheim and Fallingwater are very pure in form, but don’t carry the same soulless demeanor somehow.

Fallingwater:

Guggenheim:

Corbusier really faltered in two places. As an architect, he seemed more interested in urban and city planning on a larger scale. He felt central planning could help provide more efficient living across the entire socioeconomic spectrum. He had the specific (and ironic) goal of improving the living conditions of the lower classes. Corbusier was the original designer of the idea of tall apartment buildings with highly efficient cell-like apartments. Urban housing project planners later adopted this idea. Zoning laws and the separation of residential, commercial, and industrial spaces followed suit as well.

He also recognized the prominence and importance of the automobile in transforming not only transportation, but the places on either end. He incorporated these ideas into his city planning and helped produce Car Culture. The only person who is arguably more culpable is Robert Moses.

Corbusier hasn’t been around for quite awhile now, but it has taken decades to begin removing the cruft of bad design left in his wake. His imitators and students are just as bad, and just as focused on awful urban designs. I.M. Pei is the most obvious; he says of his Dallas City Hall design that he wanted it to “convey an image of the people.” Observe:

Right. This conveys the feeling of an architectural big brother, crafted for the government, and watching as we scurry around. Pei also designed the Boston City Plaza (known as the brick desert) and put the glass pyramid in the middle of the Louvre because it was “most compatible” with the rest of the museum. Really.

Fortunately, urban planning seems to be migrating much more towards the New Urbanism movement - away from concrete and towards diversity, away from cars and towards pedestrians. Consider this comparison between Corbusier and Jane Jacobs, one of the earliest critics of 20th century urbanism.

Corbusier:

We must create a mass-production state of mind: A state of mind for building mass-production housing. A state of mind for living in mass-production housing. A state of mind for conceiving mass-production housing.

Jane Jacobs (from The Death and Life of Great American Cities):

The necessity for these four conditions is the most important point this book has to make. In combination, these conditions create effective economic pools of use:

-Mixed uses, activating streets at different times of the day

-Short blocks, allowing high pedestrian permeability.

-Buildings of various ages & states of repair.

-Density.

It’s ants vs. humans.

The most interesting consequence of the likes of Corbusier and I.M. Pei comes from their ingenuousness. They really meant to be helping make the world better, and they followed their perspective to the extremes of their genius and ability. Corbusier famously said that “The house is a machine for living in.” He really believed it, and he really believed his perspective would help make us better.

That’s something we are called upon in our culture to do constantly; we follow our passion, we follow our beliefs. But what if our beliefs are wrong? What if we’re following the wrong problem? In a culture so built on relativism, the truthiness of the solution is what matters.

Following that line of thinking and self-centered progress is exactly what caused Corbusier to fuck things up so badly. He genuinely wanted to help solve large problems in the world: poverty, poor living conditions, inefficiency. But the solution for these things isn’t architecture. Wealth solves poverty. Wealth solves living conditions. Inefficiency is a qualitative part of the human condition and one which we should perhaps embrace more than we do in modern society, as it has amongst its positive side effects the promise of serendipity.

The next few decades will see a revolution in the planning of towns and cities, and the blight of 20th century architecture will slowly disappear. It’s the kind of revolution Corbusier wanted to kill off. “Architecture or revolution. Revolution can be avoided.” he said. Although, perhaps it’s not as bad as he thought.

The larger moral question of pursuing the truth remains. The abandonment of truth for truthiness, so easy in our modern era, needs a level of meta-thinking that is still unfortunately rarely seen. We need to build frameworks for more intellectual honesty and questioning to understand the impact of either wrong solutions or wrong problems. These all start with truth and have some sort of honestly that allows sideways and contrarian views to turn problems around. And they absolutely require meta-thinking.

Getting the meta right will be the quintessential human challenge of the 21st century.