Walter Breuning is a fascinating person I’m almost sure you’ve never heard of. Walter is 114 years old. He’s the oldest living man. He lives in a nursing home in Montana. Until very recently, he still walked daily. He still wears a suit. He’s very lucid and his memory is clearly intact.

Walter’s memory, in fact, is unbelievable. He remembers his childhood well, when they had only kerosene lamps and horses were the only form of transportation. He says you used to “carry the water in, heat it on the stove. That’s what you took your bath with. Wake up in the dark. Go to bed in the dark. That’s not very pleasant.”

Walter remembers the day President McKinley got shot as the day he got his first haircut. He remembers sitting by the fire while his own grandfather told war stories.

Civil War stories.

The Civil War is still in living memory. It may be secondhand, but it’s there. The Civil War and the time of Abraham Lincoln has always felt like something in a textbook to me. It was so far in the distant past that it wasn’t really real.

That’s the interesting thing about time: the further from the present we think - whether into the future or the past - the more indistinct it becomes. This is as true for generational memory as it is for individual memory. Events of hundreds of years ago blur together even though they themselves are sometimes hundreds or years apart. We think of Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson together generationally, but we forget that Franklin was 37 years older than Jefferson. Franklin was an old man at the signing of the Declaration. Jefferson was a young man.

The notion of living memory has been basically the same through all of human history. Living memory is what those living can remember. As that fades, the reality of existence at a given time in human history fades like ink on old parchment. Beyond anthropology, some books, and some artifacts, we can only guess at what things were once really like.

The last hundred or so years have really started to change our memory. First the daguerrotype and then the photograph. Then moving film and TV. Now, the internet. These have changed, with very little fanfare, our collective memory. We can see photographs from the 1800s. We know what Lincoln looked like. We know what street scenes looked like. We have footage from World War I, World War II, and the Holocaust. Between Flickr, YouTube, and many others, the last few years are the best documented in history. For better or worse.

I wonder how this will continue to change in the future. I love the more timeless concept behind the internet startup 1000memories. I’m glad we will have these memories to learn from in the future. But it’s increasingly our cultural responsibility to deal with this massive amount of information well. The media has become increasingly nit-picky and focused on every wrong, misstep, or change in every public figure or public policy. Pessimism sells, which is unfortunate. We need more 1000memories. More longbets. More Wikipedias.

I want to continue to remember Lincoln as a great president, not as a depressive who struggled at times with suicide. I want to remember Van Gogh more for his art than his personal troubles. I wonder if we could remember Clinton the same way?

I don’t mean to say that we should all wear rose-colored glasses. Rather, we should be understanding and realistic in our cultural attitude - we should forgive and seek to understand.. Wow, I really didn’t expect this to turn into a call for civility.

Right now there are only a few World War I veterans alive. Very soon there will be none. My lifetime will likely see the passing of the last World War II vet, the last Holocaust survivor, and the last person who remembered when Kennedy got shot. We have the ability to hold onto these memories in a way we never could before. They deserve our attention, so that we can learn from them.

Paris in 1838

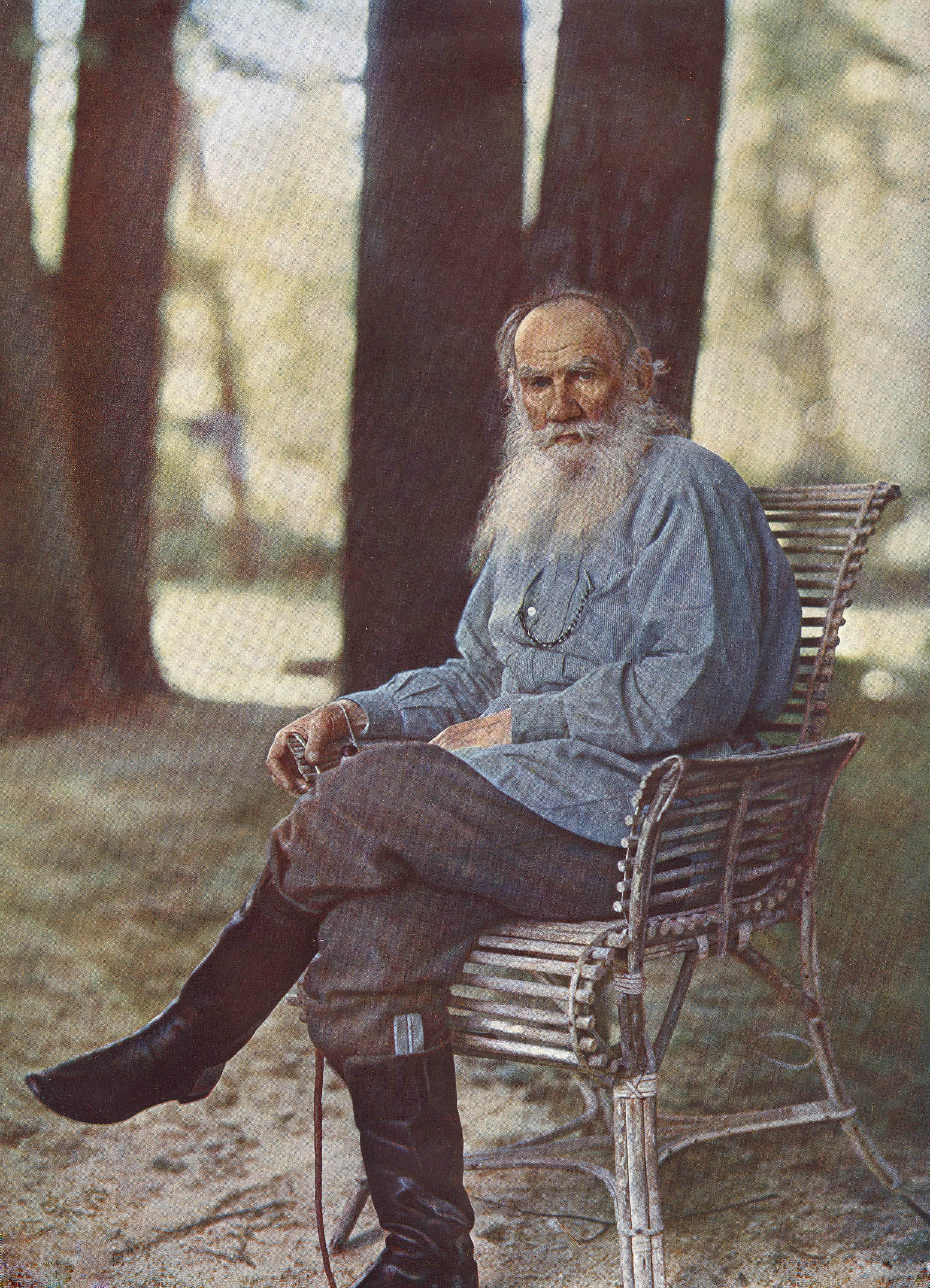

Leo Tolstoy in 1908

The Capitol in 1861