The Long View on Fossil Fuels

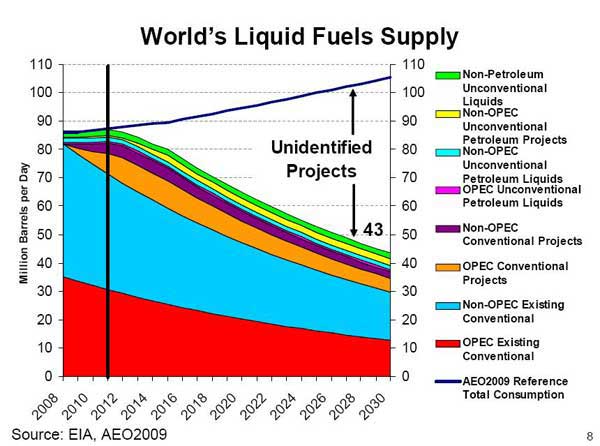

A couple of months ago I ran across this article focused around a particularly interesting graph:

And the faux harrowing subtext:

Look at this graph and be afraid. It does not come from Earth First. It does not come from the Sierra Club. It was not drawn by Socialists or Nazis or Osama Bin Laden or anyone from Goldman-Sachs. If you are a Republican Tea-Partier, rest assured it does not come from a progressive Democrat. And vice versa. It was drawn by the United States Department of Energy, and the United States military’s Joint Forces Command concurs with the overall picture.

The most fascinating thing about all of the energy conversations that exist is that they are all focused on the ten to thirty year time frame. What’s going to happen in 2020, 2030, etc. The concept of peak oil is generally considered within this context. That annotates them for me as political arguments. This is not to say that they’re directly tied to election results or specific political power. Rather, they’re focused on divvying up the resources that exist now in such a way as to ensure that the ones doing the divvying get the most.

Peak oil is not a myth. By definition, fossil fuels are finite resources. When considering the course of human history, we cannot consider them infinite. We’ve rapidly increased our technology on the mule back of oil, and going forward we have to consider the implication of that dependency.

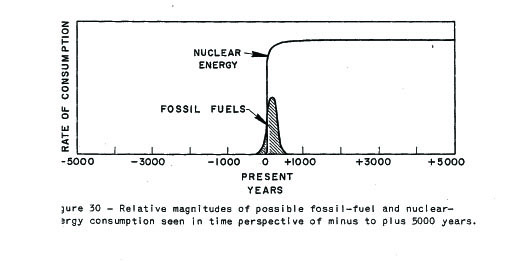

Way back in 1956, this was the principal topic of Hubbert’s initial paper, “Nuclear Energy and Fossil Fuels”, considering the extent of fossil fuels. Hubbert was using the finitude of fossil fuels as a bandstand to advocate the nuclear revolution. He was partially successful, until nuclear power got a bit ahead of itself and a few disasters piqued the public’s interest enough for politicians to back away from funding.

But Hubbert’s original contention, which we’ve largely displaced with political conversations, was that we as a species must consider alternative sources to drive support for our culture forward. Energy is the single most important consideration to our way of life. Everything else, our transportation, food production, manufacturing, clothing, leisure - everything is driven off energy. Specifically, it’s driven off a known finite resource. We don’t know the upper bound exactly, but we know there’s an end somewhere.

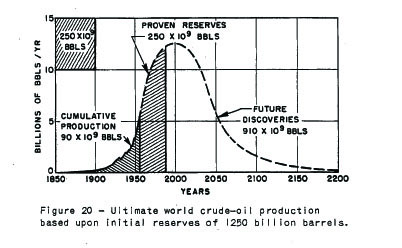

We need to get back to those fundamental points. Consider this graph from Hubbert’s original paper:

There’s a lot of similarity to the DOE’s more recent graph. The peak is a touch off, maybe a decade or two. The language is similar too: “future discoveries” and “unidentified projects”. We should consider Hubbert’s predictive power accurate. He very accurately predicted the same curves for the oil and gas production of Texas and the United States. On a global scale, we should expect the error to be slightly larger, so a decade or two makes sense.

For the long view on energy, an excellent place to start is the marvelously useless Drake Equation. The Drake Equation is an estimation for the number of civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy. The factors stated are:

- R* = the average rate of star formation per year in our galaxy

- fp = the fraction of those stars that have planets

- ne = the average number of planets that can potentially support life per star that has planets

- fℓ = the fraction of the above that actually go on to develop life at some point

- fi = the fraction of the above that actually go on to develop intelligent life

- fc = the fraction of civilizations that develop a technology that releases detectable signs of their existence into space

- L = the length of time such civilizations release detectable signals into space.

We care about fc and L.

For civilizations to continue beyond a certain point, a combination of planetary resources is necessary. Oil has convenient ties to early life, so sufficient evolution (on the order of a couple billion years) of carbon-based organisms will produce hydrocarbons suitable for energy. But additional material is important. For Earth, it’s been a combination of metals, silicon, and carbon. Elsewhere, perhaps it could be other elements.

What the materials are is largely irrelevant, but the materials must exist for intelligent life to develop technology. The larger question is the L factor: the length of time these civilizations, including ours, have the available technology.

Currently, we humans are earth-bound. We’ve had a couple hundred years with fossil fuels, and we’ve done a solid job of advancing the way of life of humanity. The third world is slowly disappearing, infant mortality is still dropping, life expectancy is increasing, and the quality of life is increasing. We can travel with relative ease around most of the planet and we can launch rockets, people, and scientific experiments out of the atmosphere and into space. All essentially based on fossil fuels for energy.

Consider Hubbert’s peak graph again. Let’s move the peak forward a couple of decades and consider the tail longer. Let’s say we have the equivalent oil resources and production in 2100 as we did in 1940. What will happen? Where will we get our energy for the at least ten billion people that will be alive then? Look out another hundred years to where most of the oil available is depleted. This isn’t that far forward, there’s less time between now and 2200 than there is between now and the War of 1812. Will humans be earth-bound? Will the earth still support all of us on our current energy? What will our future be then?

At some point, humanity will either remain earthbound with whatever resources are available exclusively from our planet, or will reach a planetary exit trajectory - a method of energy will be developed, piggybacked off our available Earthly resources, that will provide far more than we currently have.

There seem to be three possible outcomes:

We will have enough fossil fuels and time to provide ourselves a planetary exit trajectory, enabling humans to extend beyond the length of the Earth.

We will manage to have enough energy to provide ourselves a comfortable planetary history. We will move past the finite resources to be able to consume and store solar and other energies in an appropriate fashion. This energy will be sufficient to sustain a progressive technological future on Earth.

We will not have enough energy to provide a comfortable planetary history. As the finite resources we currently use peter out, we will reform into a more agrarian based society, without the continued technological progress that has gotten us to where we are.

The differences between the 3 scenarios above is completely unknown. The available resources to affect the outcome may have a hard limit, or the resources may be available for us to squander at our leisure.

Freeman Dyson talks about cultural evolution replacing biological evolution on this planet over the last ten thousand years. Homo sapiens has caused that and is continuing to drive it through our interaction with the biosphere and through our technology. It’s worth considering how that evolution can continue to drive forward beyond the next two hundred years. If it can, it won’t be because of fossil fuels.

Understanding the long view helps to inform the perspective on the ecology of our planet. Hubbert recognized this immediately in his original paper that formed peak oil theory. This is the last graph in the entire paper:

It’s worth considering that an Earth-bound humanity may be either inevitable or a positive future. If cultural evolution is driving us forward with technology, it’s also driving us forward in morality and philosophy. Either way, understanding the ecology of our environment and our energy is fundamentally important to our history as a species and should be considered as such, rather than exclusively in the short term political context of a few decades.